The good news is the trek is no longer part of their daily schedule. Thanks to Free the Children—the world’s largest network of children helping children through innovative education and development programs—Emori Joi now boasts a new well. If you’ve seen the brown-hued Mara, you’d understand the importance of the irrigation system, nevermind its impact on women’s overburdened schedules.

The custom of water walks continue, however, on these volunteer trips run by FTC’s social enterprising arm, Me to We. An educational, engagement and volunteer opportunity rolled into one, participants descend upon FTC projects worldwide to build schools, medical facilities, latrines etc. and take part in community activities. The trips aside, Me to We also sells socially conscious clothing, books, music and runs events, with 50% of profits going to support FTC’s charitable efforts and the rest re-invested.

It’s not easy running a social enterprise – more on that later – but it seems Me to We is effectively leveraging the capacity of FTC. And today in Emori Joi, it’s offering us a unique, first-hand glimpse at the work on the ground to better understand FTC’s growing impact.

An integrated model

You see, the well is a testament to FTC’s Adopt-A-Village model, a holistic approach to development focused on four pillars: quality education, alternative income projects, healthcare and clean, safe water. While other organizations concentrate unilaterally on one issue, FTC knows all too well the domino effects of poverty. Dirty water affects one’s health, which impacts educational opportunities, which intensifies disempowerment. And so goes the cycle of interdependence.

It explains why FTC’s water projects are typically constructed close to schools, so that young girls – tasked with helping their mothers with the all-consuming fetching of water – don’t have to choose between completing their duties and getting an education.

And it explains how 50-year-old Mama Jane’s property now boasts a beehive, goats, toilet, nutritious garden and soon-to-be complete brick home. Thanks to alternative income training, a group of Mamas from five communities run a Merry-Go-Round, pooling and investing their money into various projects that meet communal needs. Empowerment, sustainability – and Mama Jane’s beaming smile – are the results.

As we tour her home, Jane’s enthusiasm is infectious, her courage, humbling. She relates how, the night before the mamas received their beehives (whose honey helps purchase goats), “we couldn’t sleep we were so excited.” Upon entering her brick home, still under construction, she pleads, “Change takes time so when you see it please don’t be discouraged.” It may not be finished, “but I’m so proud,” she says. “It shows what’s possible.”

Community engagement

There is perhaps no better demonstration of what’s possible than the work of Free the Children. But they’re not doing it alone. FTC works collaboratively with community members, first determining their needs, then working hand-in-hand to meet them, fostering self-sufficiency, sustainability, instead of good ‘ole faithful, dependence. So far so good: 650 new schools and school rooms are currently teaching over 55,000 children a day; 30,000 women are benefitting from alternative income projects, and a million people have access to clean drinking water, health care and improved sanitation facilities.

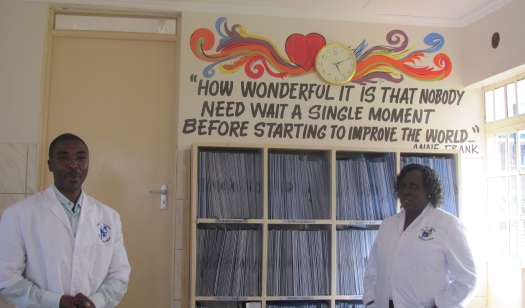

In Kenya, the Baraka Health Centre (whose new maternity ward I helped build on this same trip), one of FTC’s newest projects, serves over 40,000 community members, while promoting health education and prevention. It sits adjacent to FTC’s Kisaruni Girls Secondary School that just welcomed its second year of students.

But change is a funny beast, often inspiring its own brand of domino effect. You see, the school – whose proud students greeted us with singing, dancing and speeches – is more than an educational tour de force. It’s a model of peaceful coexistence. Aside from offering young women education opportunities – fostering ambition and self-confidence – Kisaruni is bringing together under one roof two tribes with a history of conflict, the Kipsigis and the Maasai.

Robin Wiszowaty, Kenya Programs Director, recalls the school’s ground-breaking ceremony in 2008. “It was first time in the region’s history where these ethnic groups gathered on the same plot of land for reasons other than fighting,” she relates.

There’s no denying the impact these projects are having on the ground thanks to a unique approach, devoted staff, committed partners and insatiable volunteers. And let’s not forget the contributions of Me to We. Their trips have attracted more than 1,300 participants who enjoy a unique opportunity to work hand-in-hand with community, an engagement that lasts well beyond the journey. Looking to meet a growing adult demand for customized opportunities, the organization recently constructed Bogani, a mini-village of sorts, an hour flight from Nairobi, boasting luxury cottages and tents. A similar development will be complete in India in January.

The impact of social enterprise

It’s just another investment in social entrepreneurship, the pursuit of which has proven effective, says FTC and Me to We co-founder Marc Kielburger. “Not only has it helped us achieve our goals, it has dramatically enhanced the model of what we do, how we work, how we fundraise, how we engage and how we communicate with our donors and stakeholders.” The trips also provide the organization with, “a few thousand ambassadors who are spreading what they’ve seen and done by word of mouth.”

Thanks to word of mouth, in fact, Free the Children doesn’t spend a single dollar on marketing. That means no commercials, no telemarketing, no canvassers asking you for a minute of your time. “Unlike most organizations, people can actually participate in our projects aside from just writing a cheque,” Kielburger explains.

Of course, running a social enterprise has its challenges. For one thing, many adults still don’t understand what it means, offers Kielburger. “You get a lot of puzzlement, confusion, distrust.” Another obstacle is finding staff well-versed in both the NGO and business world, who are entrepreneurial and socially engaged but can also read a balance sheet. Having just hired a training team and director, it seems they’re getting there.

Doing it right

Challenges aside, it’s evident Me to We is doing something right and can teach other social enterprises a lesson or two. For one thing, be clear on who you are…and who you’re not. “You can call yourself a social enterprise but it’s much harder to be one,” Kielburger says, noting many businesses give back a percentage of their profits but do nothing more. For another, seek help when needed. “We have had the benefit of a lot of people who’ve helped us along the way,” he offers.

Finally, a commitment to transparency is paramount. The organization, for instance, voluntarily conducts annual reports and audits, quantifying their numbers and social impact. “We take all the necessary steps to make sure that this is actually providing social value.”

Mama Jane would surely raise a celebratory glass of water to that.

Elisa Birnbaum is the co-founder of SEE Change Magazine, and works as a freelance journalist, producer and communications consultant. She is also the president of Elle Communications.