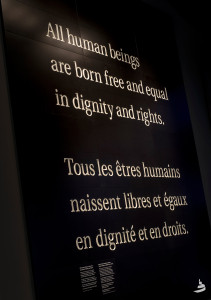

One of my more cherished memories as a student was taking an exclusive seminar course on international human rights with Canadian human rights activist, John Peters Humphrey. An author of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the man was one of my heroes. I still get goosebumps recalling the 10 of us huddled around a small table, mesmerized by the stories shared by this larger-than-life advocate of working at the UN, side-by-side with Eleanor Roosevelt, and the challenges of drafting a document that would forever codify the rights and freedoms for all human beings.

That auspicious course was on my mind last week upon visiting the new Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) in Winnipeg, Manitoba. It wasn’t just the special section they dedicated to Humphrey’s efforts at moving the human rights needle that made me reflective. It was the fact that his presence was somehow palpable – along with every other human rights champion past and present – as I traversed the expansive and breathtaking institution.

In many ways, that’s the point. Having opened its doors in September 2014—CMHR is not your typical museum, nor was it intended to be. The first one ever built to focus strictly on exploring the idea of human rights, CMHR’s mission isn’t to commemorate a specific event or group. It’s about creating a safe, inclusive space to learn and engage in dialogue about human rights (with special, but not exclusive, reference to Canada), all the while encouraging reflection and promoting action against hatred and oppression.

An ambitious mandate, to be sure. But like its visionary Izzy Asper—who pitched the idea for the museum on the anniversary of the signing of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms—the aspiration is backed by action: thought-provoking, inspired exhibits that pull you in, shake you up and set you free only once you’ve been sufficiently stirred.

The stirrings begin immediately upon entering the doors, thanks to world-renowned architect Antoine Predock of New Mexico. There are too many compelling design elements to mention here but one in particular really stood out for me. Visitors are guided through the galleries by these glowing white alabaster ramps, lit from the inside, that wind all the way from the bottom floor to the top. They symbolize the path of light through the darkness, explains my tour guide, that the route to human rights is not a straightforward one.

That the $351-million private-public collaborative project was built at a historic spot – First Nations Treaty One land and the homeland of the Métis people, a meeting place for thousands of years, is no coincidence. Bringing the world together on an important journey of engagement and dialogue at this special place is seen as a way of honouring that 6000-year-old tradition.

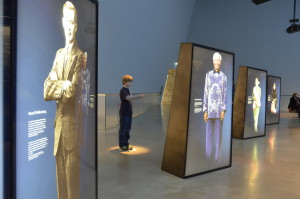

The museum’s unique approach gives many pause too. Eschewing the traditional focus on artifacts (though you will find some fascinating ones here) CMHR leverages modern technology for its storytelling purposes. It’s a powerful choice. Using a variety of tools such as poetry, music, shared discussion, digital interactive displays and theatre, the end result is a fully immersive experience.

The CMHR houses a collection of 180 (and growing) video-recorded oral histories from a diversity of people who share personal stories of struggle, strife and even empowerment. Visitors can interact with new technology and sometimes participate within an exhibit, breaking down that proverbial fourth wall.

What’s more, rather than focusing on race, ethnic group or country, the human rights stories here are centered around various educational themes – e.g. What are human rights, Indigenous perspectives, Breaking the silence, Rights today, Inspiring change etc. Each theme is then explored through the lens of topics like LGBT rights, women’s rights, children’s rights, racism, the struggles of various ethnic groups and stories from Canada’s Aboriginal communities.

When it comes to Indigenous storytelling, in fact, the curators chose powerful, even provocative material. There’s “Trace”—a 30-foot original work by Canadian artist Rebecca Belmore made up of 14,000 clay shards hand-pressed by hundreds of children and adults. Strung together to resemble a giant hanging blanket, the piece is meant to reflect Indigenous concepts of land and place. The ReDress Project is an art installation by Jaime Black made up of empty red dresses on hangers, encouraging people to think about and discuss violent crimes against Indigenous women. And in another gallery sits the Bentwood Box. Carved from a single piece of red cedar, the artwork by Coast Salish artist Luke Marston was used during hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission exploring the tragic legacy of Canada’s Indian Residential School system.

The museum’s overarching focus on education is manifested by a variety of initiatives. The Canadian Teachers’ Federation (CTF), for example, partnered with the museum to create a comprehensive national toolkit on human rights for classroom teachers. That the building was filled with engaged and vocal students the day I visited—fully participating in activities and discussion, pen and notepads in hand—gave me reason to believe they were doing something right.

Talking about doing it right, not surprisingly, CMHR recently won four awards including two gold prizes, in one of the world’s most prestigious competitions for innovation in digital media – the MUSE awards, alongside renowned institutions like the Smithsonian and the 9/11 Memorial Museum. The Lights of Inclusion game—an interactive activity that invites visitors to interact with coloured lights using motion-tracking sensors—won silver. Its mobile app – the first of its kind for a museum that offers a fully accessible self-guided tour using audio, images, text and video (along with a mood meter and panoramic views from atop the museum’s Tower of Hope), won gold.

Perhaps my greatest takeaway from the visit was having the capacity to examine human rights from a variety of perspectives and lenses. Every visitor leaves with a better understanding that, like those white alabaster lamps signify, human rights does not offer a straightforward, standardized narrative. At times it’s deeply personal. It’s messy and complicated. And it can demonstrate humanity’s darkest hours as well as its finest achievements all in one sitting.

People are often asked to put themselves into others’ shoes. The CMHR doesn’t request patrons to do that – it just makes it a necessary outcome, if even for a moment. Humphrey would have been proud.

Elisa Birnbaum is the co-founder, publisher and editor-in-chief of SEE Change Magazine, and works as a freelance journalist, producer and communications consultant. She is also the president of Elle Communications.