What do you do when it feels like your world is being swallowed up due to an environmental disaster? Who do you turn to when your leaders seem oblivious or disinterested in the challenges you and your community are facing? Two documentaries at this year’s Hot Docs Festival reveal that the answer sometimes lies at the grassroots level, in one changemaker willing to go the depths of the earth in order to save it. Along the way, they also serve to demonstrate the consequences that can arise when greed, politics and the bottom line outweigh a regard for human rights and justice.

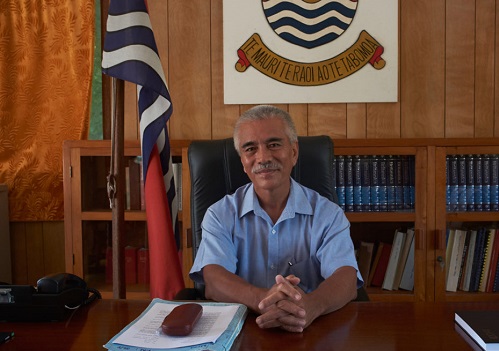

In Anote’s Ark, we follow the efforts of Anote Tong, former president of Kiribati, an island “at the centre of the world, in the middle of Pacific Ocean” as he tries to save his home from being swallowed up due to the rising sea levels. Directed by Montrealer Matthieu Rytz, the documentary is, on the one hand, an inspiring homage to the tireless activist and his fight to the end. On the other, it’s a frustrating depiction of what happens to that tree that falls in the forest, with no one around or willing to yell “timber”.

So isolated from the rest of the world, you couldn’t fault anyone for thinking that Kiribati would be protected from the challenges that the rest of the world faces. But they’d be wrong. “We’re not immune to climate change and we must not longer stand on the sidelines,” says Tong, as he looks despondently at the devastation caused by a hurricane that left houses and villages underwater, a weather narrative that many predict will be become norm in these parts. Tong, in fact, believes that, by the end of the century, the 100,000-plus residents of Kiribati will soon be looking for a new place to call home. It’s this message that Tong is shouting from the proverbial rooftops as he travels the world in search of support.

We see him at the COP 21 Climate Change Summit in France where he receives the endorsement of political leadership. But then Donald Trump pulls out of the UN-backed agreement and others seem to be paying it more lip-service than actual support. And the initial energy from that Paris meeting seems to be slowly dissipating, much to Tong’s dismay. “This is an act of war and we don’t have the means to counter,” he says despairingly. To forestall what he sees as inevitable, we see Tong purchasing land for on Fiji and even exploring the possibility of partnering with a Japan firm that promises to build a $50-billion floating city.

While Tong continues to fight, we follow Sermary, a mother of three, who’s had enough. She moves to New Zealand, her husband and kids following a few months later. Soon, pregnant with her fourth, we catch a glimpse of what happens when families are uprooted, communities are dismantled and life begins anew. Sermary and her husband acknowledge that their newborn may never know the wonders and delights of her parents’ home. The greatest cost of moving, they explains, is the loss of their Indigenous roots and the spiritual essence that makes Kiribati so special. “We will lose our distinct culture,” echoes Tong.

At the end of the film, both Tong and Rytz joined the audience for a Q &A. When asked how he thinks the situation will ever improve, Tong replied that making it an election issue is the only way. “I guarantee politicians would be on board if it was,” he shared, adding cynically that the greatest champions of democracy are those who are good at distorting it.

In Grit, we visit the communities of Sidoarjo, of East Java, Indonesia where in 2006, oil company Lapindo was drilling for natural gas and struck a pocket of mud, unleashing a volcanic disaster. The mud tsunami that followed killed residents, displaced over 50,000 people and submerged communities.

The mudflow continues today and is expected to flow until 2030, emitting its grit and grime across the landscape and serving as a constant reminder of the impotence of the powerless.

At the heart of the film is Dian, a 16-year-old activist who has been displaced from her home by the tsunami, along with her mother, sister and father who we never meet as he died a year earlier by a cancer that the film intimates may have been caused by the toxicity of the mud flow.

We watch as residents fight, to no avail, to win compensation for their damages and struggle to make ends meet in the meantime. To wit: Dian’s friend is forced to drop out of school in order to help support his family while his father tries to sell “souvenirs” of the explosion for sustenance. Dian’s mother, meanwhile, moonlights as a “tour guide” to those interested in learning about the history of the once-vibrant communities.

The displaced are dismissed in equal measure by political leaders and the CEO of Lapindo who, not surprisingly, is fully enmeshed in the political landscape. In one captivating interview, he greedily recounts how his company made residents prove, through documentation, that their lost homes in fact belonged to them. Who thinks to bring their paperwork when fleeing a mud tsunami? In another telling scene we see him singing Frank Sinatra’s My Way. “I love this song, the lyrics,” he says with a broad smile. Indeed.

Dian sees the bigger picture and understands how politics can dehumanize and take sides when money is on the table. And she refuses to stay silent. She becomes, instead, the community advocate, fighting for justice. “My children are the future, I don’t have more hope for me,” says her mother, acknowledging her daughter’s battle.

As the mud continues to rise, the residents of these Indonesian communities face the same fate as the citizens of Kiribati: homelessness. They share another narrative as well: the uphill battle against greed and indifference. In Grit, the government has even cut off research in the area meant to determine the long-term effects of the disaster. Money talks. Businessmen with their hands in politician’s pockets speak louder than the poor and displaced. The tree has fallen once more, its limbs submerged in mud and grime. But not one is listening.

In one of the most powerful scenes, at the top of the documentary, an artist by the name of Dadang Christanto, who has spent his career honoring the countless victims of political violence and crimes against humanity. produces an installation aptly titled Greed, consisting of dozens of mud figures standing shoulder to shoulder in the mud, palms facing upwards. As the film continues, we witness tourists and residents alike visiting the spot, taking pictures (it even stands as a backdrop for a model’s photo shoot), placing tokens in the figures’ hands. And we watch the mud rise as the victims continue to wait for their compensation. By the end of the movie, the statues are almost fully covered in grime.

Ten years after their first claim, the families who lost their homes are finally compensated when the government lends Lapindo $60 million to meet its wrongdoings. With the money she receives, Dian’s mother pays for her daughter’s law school education. Which is a good thing, as we learn that Lapindo has started drilling again to pay back its government debt. Corporate greed continues but one fighter will be ready to support her community in the years ahead.

As for Tong’s fight? It continues as well. He’s doing all he can, setting up meetings, carving partnerships and traveling the world to tell his story and that of his people. “No one wants to believe they won’t have a country in the future,” he says of the residents he’s fighting for. “It’s about my own grandchildren and their future. Where will they be? That’s the issue.”

Elisa Birnbaum is the editor & publisher of SEE Change Magazine and the host of its podcast. Her first book, In the Business of Change, profiling social entrepreneurs around the world tackling challenges in their communities, was published this summer.