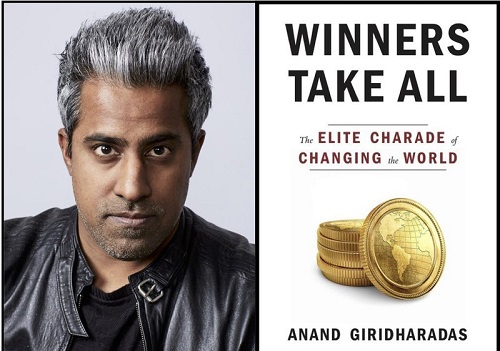

Every once in a while a book comes along that really gives me pause, causing me to question assumptions and giving my worldview a serious shake. Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World is one of those books. The questions and issues raised in the book weren’t necessarily new – some I had been contemplating myself – but the in-depth exploration author Ananad Giridharadas offers infused those issues with newfound clarity and credibility that make it now difficult to see things any other way.

To listen to the podcast interview with author Anand Giridharadas click here

At the crux of Giridharadas’ book is what he calls the MarketWorld, “a network and community but also a culture and state of mind.” They’re the group of global elite who, often with great intentions are focused on tackling intractable social challenges in ways that promote the twin ideologies of “win-win” and “doing well by doing good”.

Problem is, despite their often well-meaning objectives, Giridharadas argues that the MarketWorld changemakers are only interested in the type of social change that preserves their status quo, that doesn’t upend the systems that maintain their social order and their roles in it. As Giridharadas puts it, they support social change so long as it’s done in market-friendly ways that don’t undermine the power imbalance.

It’s in this world where market forces and entrepreneurship are promoted above all else as the answers to social problems. After all, that’s the language of empowerment in the MarketWorld. But, oftentimes that discussion takes place without the actual input of the very people they’re trying to help. Rather, they happen in an elitist bubble of sorts far removed from the realities on the ground.

For years my writing has focused strongly on the power of entrepreneurship in its ability to raise people up, toward a stronger, more sustainable path forward. I still believe that helping people stand on their own two feet is essential to that narrative. But I have always maintained that the people you are trying to help should be included in the conversation – central to it, in fact. The most successful social change efforts I’ve written about involved social entrepreneurs working with communities, not just in them, ensuring they’re an indelible part of the solution.

In one chapter Giridharadas takes a look at Silicon Valley’s unique approach to social change. Theoretically, technology has the potential to equalize, to level the playing field, to democratize. But it doesn’t always work that way. We meet Jane Leibrock who worked at Even, a company with a well-meaning mission – to stabilize the income of a growing number of Americans experiencing volatility. The Silicon-valley solution was of course an app. For a fee, the app would help people stabilize their cash flow by topping up their funds when needed and taking a bigger piece when they didn’t. The thinking was social challenges could be best tackled while building a business. Win-win.

Except it’s not. When Leibrock when out to meet with prospective customers – folks that Silicon Valley seldom interacted with otherwise – the wake-up call was intense. She saw a lot more clearly the deep-seated and intricate systemic challenges that many Americans face each day, from healthcare to student debt, from precarious work to food insecurity. All the changemaking innovations, all the apps in silicon valley hadn’t moved the needle in addressing those challenges. But when elite changemakers are so far removed from the realities on the ground, who can expect any other outcome?

In another chapter, Giridharadas looks at the rise of elite conferences focused on solving global challenges (particularly the slew of them scheduled during UN week in New York) that bring together like-minded MarketWorld participants and panelists. Again, their heart may be in the right place but, not only are they far removed from those they’re trying to help, one need only look at the agenda of each conference and the panelists chosen to see that their view of social change is limited to a well-preserved paradigm (and let’s be honest most conferences price the average person out of their affairs, ensuring the conversation is restricted to the select few).

Seldom will you see panelists at these conferences dispute each other’s opinions, question the status quo. And for those who dismiss these conversations as benign, with little influence on public policy or politics, think again. These conversations are political engagement at their finest, dictating which issues are relevant, which aren’t, and ensuring we avoid any questions that threaten the balance.

Likewise, Giridharadas addresses the rise of thought leaders, well-paid, highly sought-after, many of whom end up speakers at these elite conferences and venues like TED. To be successful as a thought leader, Giridharadas puts forth the idea that you must follow certain rules: don’t talk about root causes of issues or fundamental systems change, offer hope and actionable insight – and don’t ever be political. With these thought leaders setting the stage for how we feel about social change, how can the status quo be anything but maintained?

Problem is if we don’t address root causes of issues, such as income inequality, social inequity and power imbalances, how can we ever tackle them head-on?

On a positive note, Giridharadas does highlight a number of elites who are starting to question these realities. Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, for example, caused a stir when he wrote about the need to reduce inequality (as opposed to the less threatening focus on poverty reduction). We meet Andrew Kassoy, co-founder of B Lab, the non-profit that offers businesses with B Corp certification that affirms a rigorous social and environmental analysis of their practices. Despite all the achievements with B Corps, Kassoy had come to question whether he could do more. Sure, it’s important to help companies do good but isn’t it even more relevant to make it harder for companies to create harm? Would real systems change be possible without that motivation?

The timeliness of this conversation is not lost on the reader. As Giridharadas argues, by not challenging the status quo, elites are effectively complicit in the very problems that they’re trying to fix. And by not including the insight, perspective and opinions of those they’re trying to help, elites have effectively shut out a significant portion of our population.

That’s not just a problem when it comes to effectively tackling our social issues; it has also led to resentment, anger and, yes, the rise of populism in American and the world. Giridharadas does end the book with some hope though. It is possible to change course, he believes. But only if we look to solutions from the bottom up. Instead of focusing only on markets and a changemaking elite, we need to work with and strengthen our democratic institutions. If they’re broken fix them, he says. It’s only through public action that true social change can be fought and won.

Elisa Birnbaum is the publisher & editor of SEE Change Magazine and the host of its podcast. She’s also the author of In the Business of Change: How social entrepreneurs are disrupting business as usual