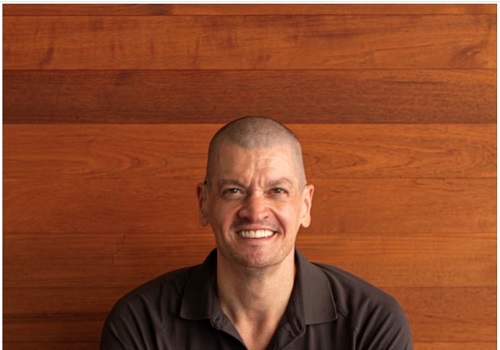

Chris Soukup’s company has been pioneering accessible communication technologies for the deaf community for 50 years. We were first introduced to Soukup and Communication Service for the Deaf (CSD), in 2018 when we published this piece. Today, Soukup continues to challenge conventional thinking around what is possible for inclusive and equitable communications. To wit: he is part of a coalition advancing new federal legislation (the Communications, Video & Technology Accessibility Act) to ensure accessibility standards for deaf and disability communities keep pace with essential emerging technologies (augmented reality, robotics, advanced machine learning, spatial computing, etc.).

What’s more, Soukup and CSD recently launched a new initiative designed to address some of the more difficult barriers for the deaf community. ASL Now is a seamless one-to-one direct video calling solution that removes the need for any third-party sign-language interpreter. ASL Now not only delivers deaf individuals a more equitable and individualized customer experience with enhanced privacy (important for calling your doctor, bank etc.) but it’s also good for business, increasing customer satisfaction and reducing call time by as much as 42%. ASL Now is successfully partnering with several leading organizations, including the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, Google and Comcast’s Xfinity.

SEE Change spoke with Soukup about his many years of innovative work in the space, his exciting new initiative, and his vision of creating equitable and inclusive opportunities for deaf communities in a world that is increasingly automated.

Let’s re-introduce our readers to CSD. Tell us how your company has been leading the way in inclusive communications for the deaf community?

Communication Service for the Deaf (CSD) opened its doors in 1975 after receiving a $12,000 grant from the State of South Dakota. From the beginning, CSD played an integral role in advocating for and delivering accessible communications solutions. In the early years of CSD, this work revolved primarily around community-based sign language interpreting services and TeleType (TTY) equipment distribution and repair. A TTY is a device that was first developed in the 1960s as a way for deaf people to communicate in a text-based format with one another over a phone line. The early forms of this machine resembled a typewriter with a compartment for attaching a telephone headset to transmit signals that the machine could convert into text. The limitation was that a TTY user could only call another TTY user.

CSD was a pioneer in the developing a process for TTY users to interface with a call center to place and receive voice calls. This eventually came to be known as Telecommunication Relay Service (TRS) which CSD provided statewide in South Dakota in 1988. After the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990, we partnered with Sprint Corporation to offer TRS nationally. CSD parlayed its success with TRS to further innovate and developed the capability to connect sign language users with an interpreter using the first video conferencing systems in the late 1990s. The use of video interpreting was nationalized in 2001 by CSD and is known today as Video Relay Service (VRS).

Importantly, over the past decade, CSD has been advocating for a new form of inclusive communications known as Direct Video Calling (DVC). It’s a partnership with corporations and government agencies to provide customer service directly by connecting a deaf person with a representative who can communicate in American Sign Language (ASL). DVC provides a seamless and fully inclusive experience as no third-party is required. With DVC, as we have throughout our history, CSD seeks to challenge convention and we remain relentless in our pursuit of a truly equitable communications experience for deaf people.

You talk about the dichotomy between the medical model and cultural model for the deaf community. Explain

There’s a perspective that disability is a “defect” and something that society needs to strive to “cure.” People who have disabilities need to be accommodated. This is essentially what is known as the medical model of disability. The prevailing perspective from within disability communities is that disability is a fundamental and inevitable part of the human experience, that our biological differences are a part of the rich diversity that exists within our world.

People with disabilities have abundant talent and a unique lens that is meaningful and creates extraordinary value. The work is not to “cure” but to recognize that the root source of the disability is a society that is inherently not designed to be inclusive of the spectrum of human biodiversity. This is the cultural model of disability.

Can you describe the severity of inequities/barriers deaf people still face today and how you are addressing these inequities and leading change?

Despite significant advances in making the world more accessible to deaf people through innovations in communications and technology, deaf communities continue to experience pervasive economic disparity. More than half of the deaf population is unemployed and those who are employed often work in spaces where they face barriers, bias, and discrimination preventing them from thriving in their careers. CSD has long been engaged in combating this reality by investing in the deaf entrepreneurial ecosystem, by partnering with government and corporations to create pathways to employment, through the development of training programs, and engaging with the national media to spotlight the talent and success of our community to chip away at false perceptions of what deaf people can achieve.

What is ASL Now? Why is it needed and how is it transforming communications for deaf and hard of hearing people?

ASL Now is CSD’s Direct Video Calling (DVC) solution that allows a deaf person to make a direct video call without the need for a third-party sign language interpreter. A specific example that I will share has to do with crisis hotlines. These resources are powerfully impactful at reaching and supporting people in a time of profound need. In the past, the only way a deaf person could reach a hotline for support was using a relay service. The level of empathetic human connection that is possible through a third-party relay is substantially lower than what is possible by connecting with a human being directly.

We believe that truly equitable communication is created when a deaf person can connect directly with a sign language user face-to-face to resolve their needs—whether they’re in crisis, trying to resolve an issue with their tax filing, discussing matters with their healthcare provider, or having issues with their internet service.

This is the spirit of what the ADA was intended to achieve – a communications experience for a deaf person that is fundamentally the same as the experience of a person who can hear. This is what DVC delivers. We have been fortunate to partner with several corporations who have demonstrated their commitment to deaf communities by investing in programs to offer customer service in sign language. One exceptional example of these partnerships is our relationship with Comcast to provide nationwide sign language customer support for Xfinity internet customers.

Please share your thoughts on how today’s AI world and the automation of customer service is impacting the deaf community

Increasingly, companies are rapidly adopting and incorporating AI systems into their customer service organizations to automate processes and to reduce the dependency on live operators. The primary motivation in doing this is to eliminate overhead costs and increase their company’s profit margins. From a financial point of view, these investments are understandable but, unfortunately, they create new barriers to access for deaf people. AI systems are not proficient at facilitating third-party calls from a deaf person who is using a relay service.

So, in many respects, the accelerating move towards AI adoption is a step backwards for the deaf community specifically in the customer service arena. We are encouraging companies who have made these investments to segment out a process for supporting their deaf customers using Direct Video Calling (DVC) to provide an exceptional and inclusive experience.

What is your vision for the future of accessible and inclusive communications?

AI has been a double-edged sword. While its adoption creates some immediate, new barriers in the short-term, we do see the promise and potential of AI and large language models (LLMs) in supporting future innovation that can be beneficial to deaf communities. Specifically, there is work that has already begun to leverage AI to accelerate the development of facial- and gesture-recognition technology. The application of this emerging technology is the development of sign language recognition software, which someday will be adept at translating sign language to voice and text.

Those applications will meld with another emerging technology that uses AI-based human-like avatars to translate voice and text to sign language. We are most likely five to ten years away from seeing this technology become commercially available and probably fifteen to twenty years way from a fully mature product. But, some day, in the not-so-distant future, deaf people will be fully autonomous and free to interact with the world in everyday situations using AI-based technologies to translate sign-to-speech and speech-to-sign.

Chris Soukup is a senior leader and advocate for deaf and disability communities. After Chris graduated from Gallaudet University in 2001, he started working at Communication Service for the Deaf (CSD), the world’s largest deaf-led social impact organization, in a community-based role. In 2014, he was appointed CEO of CSD. Over the past decade, his many achievements include: leading CSD’s global transformation to become a fully virtualized organization; the development of a disruptive software platform for sign language interpreting service delivery; the creation of the first social venture fund dedicated to deaf and disabled entrepreneurs; the launch of a jobs marketplace for deaf and disabled professionals seeking contract work and full time employment opportunities;