As things go, I am sipping on my third tea of the day while looking at the flashing icon on my phone indicating the charging has been abruptly interrupted and find myself wondering for how long I’ll be able to continue to type away on my laptop before its battery runs out.

A common occurrence here, electricity shortages have been as much part of the weekly routing as laundry activities. I think to myself how ironic it is that I have moved here upon receiving a job offer from a company that specializes in renewable energy development. Nevertheless, for whatever little time I’ve had here, I have learned that such contradictions are more the norm than the exception.

Where is “here”, you may ask? Well it is Delhi, India; this is not the first time I’ve lived in this country. In 2009 I was working here for an NGO that specialized in providing education and support to street orphans. Yet, this time it’s different: I received a call while I was visiting my mother in Italy from the company’s CEO asking me to be in India within two days. Though I am no stranger to moving to new and exciting places, the short notice meant that I had to radically change my life in what felt like a blink of an eye.

Now I find myself working for a company specialized in solar power. In many ways, this has brought me back to ponder on my previous run with India in 2009. At that time, I landed in a virtually unknown location with not so much as an acquaintance in the entire country. Difference being, while the first time involved a small plane landing on what I could only describe as a field, the second was in the bustling metropolis of Delhi. In 2009 I found myself on a small minivan chugging along the countryside to some middle-of-nowhere place I could not even pronounce. This time I went straight to the heart of one of the most prestigious neighborhood in the country.

My room during the first experience in this country was a modest single bed affair with little more than a cupboard and what looked to me like a bathroom you’d find on a fishing trawler (that story is for another time). In complete antithesis, my current room boasts a gargantuan kin-size bed, air conditioning a nice bathroom and all the nice perks that would come with a fully furnished hotel room. Working for an NGO in 2009, life was certainly something different from what I had been previously used to, I found myself shoved in front of a class of 60+ student handed a woefully outdated book and was told to teach English, geography to just mention a couple of subjects. The orphanage was located a 30-minute ride away from the nearest significant town. It was the first time a foreigner would stay at the location for more than a couple of hours and living there was unheard of. The facility was simple, about four two-story buildings dedicated to living accommodations for the children, an open structure for eating and a school. The land around the premises was dry and punctuated with farms, a very nice sight at sunsets.

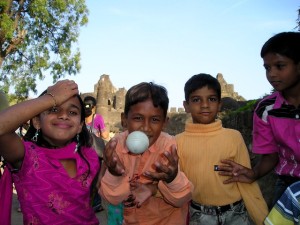

Soon my activities expanded beyond the teaching routine. I begun driving the very old and rusty tractor for irrigation with an average passenger capacity of 20 children, played on the school’s football team and somehow was made team captain certainly not through any prowess in the sport and even got into the habit of telling a very improvised bed-time stories to the children in the evening. Though it all sounds quite wonderful, there was an inherently dark side to the place: all of the children had been orphaned at a young age and some were HIV positive. While these facts occasionally crossed my mind, for the most part it seemed more like a distant thought when confronted with the sheer positivity and joy most of these children would constantly expound.

At the time, as an idealistic 18-year old who had lived a relatively sheltered life, never would have I been able to conceive the sheer amount of pragmatism, if not outright ruthless utilitarianism, that is required when working in countries where living conditions are so terribly inadequate. The thin veil of idealism I came to the country with quickly dissipated when confronted with the realities. On an ride into the giant slums of the nearby city one of the organization’s jeeps caught my attention. I walked to the empty vehicle and wondered where its occupants had gone. I peeked into the adjacent house only to see one of the organization’s nurses tending to what appeared to be very undernourished children. I asked what was going on and she briefly, and abrasively (I presume I was an encumbrance) told me that the organization could only take in one of the children. HIV medication was a limited resource and only so many could be treated.

I realized that this house was no place for highfalutin ideological standards and the choices to be made was simple yet quite heartless given the opportunity cost. Needless to say, the decision was made and one child was left behind whilst one was given an opportunity to have a full life.

I write this now from behind a corporate desk, though as companies go, we would most likely not be rated amongst the so called “bad guys”. In fact, providing solar energy is far from a malignant enterprise; in a country where the equivalent of the population of the United States – around 300 million – do not have access to any kind of electricity and have been in such a condition since the dawn of time, solar power has proven itself to be valuable solution in this regard. Yet, while both of my experiences in India can be considered steeped with ideological goodwill, I quickly came to realize that, even the most idealistic companies and NGOs share a the simple truth: when confronted with a reality on the ground, ideology is inevitably relegated to the status of luxury if not an outright burden.

Though I may be helping provide access to one of the most important resources for a human being today, difficult choices must be made. In most cases, land where solar plants are constructed is occupied by farmers. In fact, India’s landscape is highly populated making any sort of construction very difficult. In some cases a farmer will lose his/her livelihood to a new project; yet the benefits that such a project would bring to the local community are immense and invaluable. Thanks largely to my first experience in this wonderful, albeit maddening country, I find myself a lot better prepared for the realities I am constantly confronted with.

Ultimately India is the embodiment of contradiction. Just as working for a power company with no electricity may be one, so are entities that are associated with “good” who find themselves making some of the most cold, calculative and sometimes ruthless decisions. Yet it is this very fact that has taught me some invaluable lessons that I will forever take with me: what is needed is a cool head and a strong pragmatic determination to get through the day. That is the only way we can hope to make any difference.

Alessandro Medri a new York Born Italian American, conducted his studies in the UK and Canada specializing in economics and political science. He has lived in a multitude of countries around the world ranging from Italy to Hong Kong. Currently working in the Energy sector for an Anglo-Indian company.